August 2025: Stablecoins are not for Americans. They’re for everyone else

The Great Weirding: Why it's taken so long for Americans to get stablecoins

I only really got what stablecoins were for in the last couple of years, and there are a bunch of things that have been obvious to others that I’m pretty late to. Hosting A Very Stable Conference earlier this year threw those things right in my face. The biggest one, and the one that kicked off this essay (and a couple more) was the realization that fiat backed stablecoins specifically (and probably a lot of onchain products in general) at least in the short to medium term are not for Americans [1] (and to a slightly lesser extent, citizens of 6 of the G7 countries except Japan); they are for everyone else.

For Americans, Fiat >= Stables

For the use cases around money that most American consumers experience every day, along with the attributes that they care about, stablecoins are not yet better than fiat. I’ve long thought that to compete in money products you need to either move money faster, pay more yield, or enable lower cost.

Speed: most American consumers have access to instant (or near instant) payments on most of the transactions they do everyday, with the counterparties they frequently interact with. Between intra-bank payments, Zelle/Cash App/Venmo/Paypal, and fednow/RTP/same-day-ACH, and payment cards, for most of the transactions American consumers experience every day in 2025, speed is not an unsolved problem the way it was a decade ago. You might say that if 100% of Americans were on stables then they’d all have instant, but then that's true for all the other instant rails, so the statement does not mean much[2]

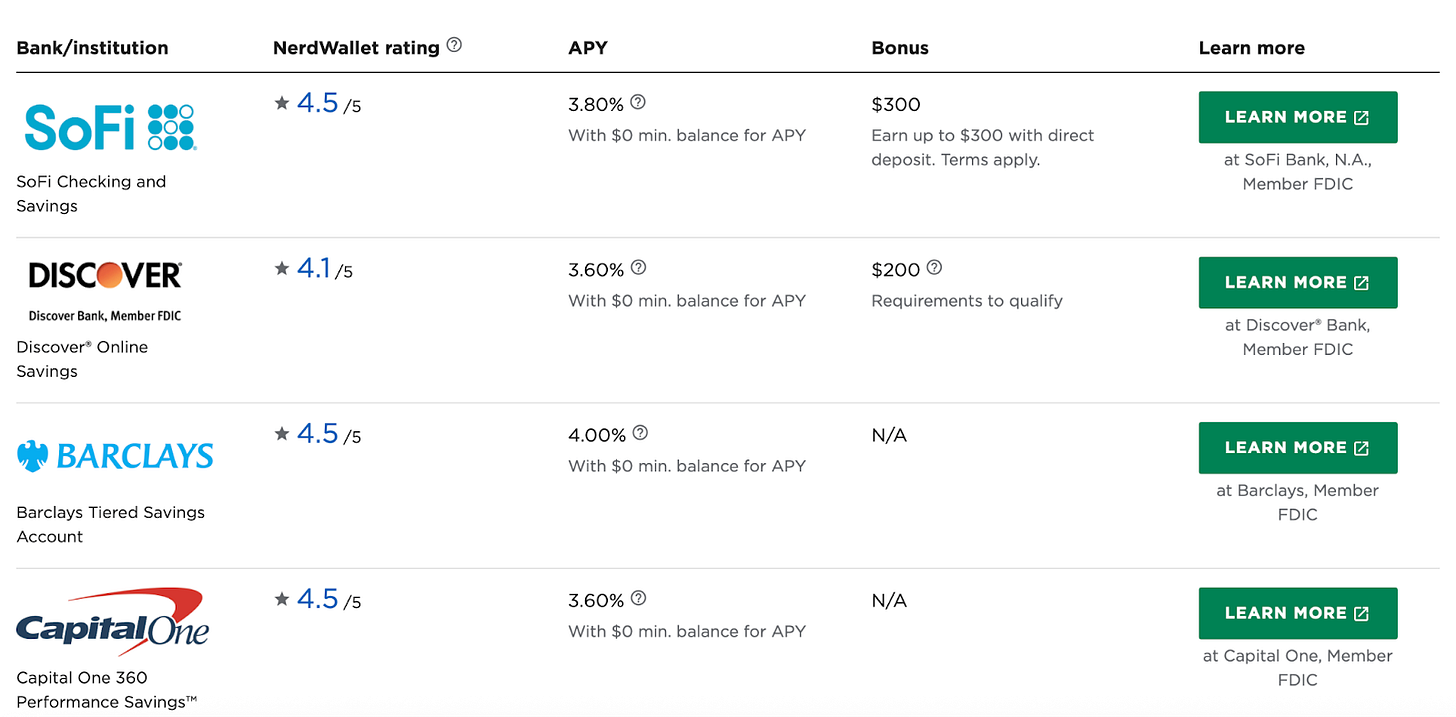

Yield: American banks and fintechs already compete ferociously on yield. Fiat backed stablecoins all (today) earn yield in large part from buying “risk free” securities (ie US Treasuries). They literally can’t (sustainably) pay you more than that. Today (August 2025) you can get those 3.5% - 4% yields with a US checking account from several banks.

Fees: this one’s a little harder to parse/compare but fiat transactions and accounts aren’t free but neither are stablecoins. Both fiat bank accounts, digital wallet providers and stablecoin issuers subsidize consumers to hold and transact funds in different ways, and in both realms it is possible for consumers to have a “free” experience. These experiences are funded in a variety of ways, and I don’t mean to discount this. I’m more just saying that most American consumers already have a way to get a “free” “checking” account and “free” money movement in and out of that checking account.

Loans: unsecured loans for American consumers are available at hilariously reasonable rates (by almost any measure both geographically and historically) and have been in fiat space for a long time (and much less plentiful elsewhere). Unsecured lending onchain is not really a thing.

If you’re a consumer in the US with access to a Chase bank account (which is most consumers), you have it pretty good. Could be better, but I can’t point to an onchain consumer financial instrument for consumers that’s so much better than Chase that the average Chase customer would switch. And for the customers Chase wants to keep? No chance. Chase moves trillions per day (this includes lots of different transaction types so it’s not all “payments”) across a wide range of transactions, and is insanely proficient at cross selling consumers. Whatever else you might say about them, they have to be pretty performant to do that well. If you’re building financial products targeting the average US consumer, Chase is who you’re competing with. And the other competitors both in the neobank/challenger bank space, and traditional incumbents, are all ferocious.

If you work in payments, in the US market, this dynamic is viscerally obvious. I think it’s at least part of why a lot of payments leaders dismissed/ignored stablecoins until relatively recently. But it made me blind to the possibilities.

For everyone else, Stables > Fiat

If you’re American, as of today, the instruments and transactions available to you in the fiat world are just as good or better than onchain generally, or in stables specifically. This might change in future, but in mid 2025 it's definitely the case. For a large portion of the rest of the world, this dynamic is not true, and has not been for a long time. If you live in a country that has experienced inflation or currency volatility in your life time, stablecoins give you something that is better than most financial products your local banks offer to retail consumers. That thing is not yield, or transaction speed, or low fees; that thing is stability, in the form of dollars. That thing is assurance that your $100 will still be worth $100 in 2 weeks, and (at least for self custodied products) it’s much harder to seize or freeze than your local bank account.

Most senior professionals working in payments in the United States, have never in their adult lives had to experience currency instability personally in their day to day. If you’ve lived pretty much anywhere in the US for the last 40 years, you’ve basically never had the exact same loaf of bread cost $5 today and then $10 two weeks later. Same is true for most staples/groceries. Americans (and Westerners to a slightly lesser extent) take currency stability for granted. But for many people in the world over the last two decades, inflation (or broadly volatility in the prices of every day goods) has been the default state, and stability is a feature you viscerally crave. Stablecoins give you access to . . stability. Stables introduce a benefit Americans (and to a slightly lesser extent, people living in western nations) take for granted, to the rest of the world. This is one reason I think the best way to describe what stable coins are today in particular (beyond being a settlement currency onchain) is a vector for exporting dollars. [3]

For people living with currency instability that pierces through to volatility in the prices of goods, stablecoins literally increase their purchasing power. For Americans, stablecoins don’t.

Consumers are adopting stablecoins faster than enterprise

We launched the conference with the hypothesis that very soon companies like Apple (mainstream consumer brands that everyone knows) would adopt stablecoins in core enterprise workflows. But the reality is that the Fortune 100 is very well banked and for the most part stable coins are not better than the banking system they have access to. They generally have high quality banking relationships in the geos where they operate, sophisticated finance teams and access to the best rates (on deposits, fx or yield) from all their banks.

I came away from the conference understanding that I had missed a really core story which is: billions of humans have only ever used a volatile local currency [4] their entire lives, and now they can just get access to dollars in very small amounts for reasonable conversion rates without permission. For this group, stablecoins are insanely disruptive. I wrote about this years ago and I think I just didn’t realize how big it could get:

“In contrast, prior to the existence of cryptocurrency, it was (and still is) fairly common for wealthy individuals in poor countries to hold foreign currency (typically USD, GBP or EUR) as a mechanism for savings. As a treasury/FX trader, I used to think (and I still think) that a good heuristic for a country’s economic trajectory is to look at where the country’s rich put their wealth. Wherever wealth is exported (e.g. if the move when you get rich is to immediately buy New York or London real estate) is a signal that citizens are afraid of wealth seizure (either explicitly by confiscation, or implicitly by inflation).

Governments [will] hate this because it creates natural selling pressure for their home currency, but a fiat-backed stablecoin pegged to the US Dollar or Euro (with real assets under management) that is permissionless and effectively beyond the ability of the government to stop you from buying, is simply a digital asset substitute for a real use case that exists. Before stablecoins, you had to buy dollars from a bank and keep it in a bank account (which has its merits) but the bank could also a) just refuse to sell them to you (which is what happened most of the time), b) charge you a ton of fees to buy or hold it or c) be forced by the government to convert at a fake exchange rate or limit how much you could buy or own. Even in today’s environment, if you’re in the US you should try going to your local Bank of America or logging into your Chase mobile app and try to buy some euros, and it will become blindingly obvious how unsupported this is.”

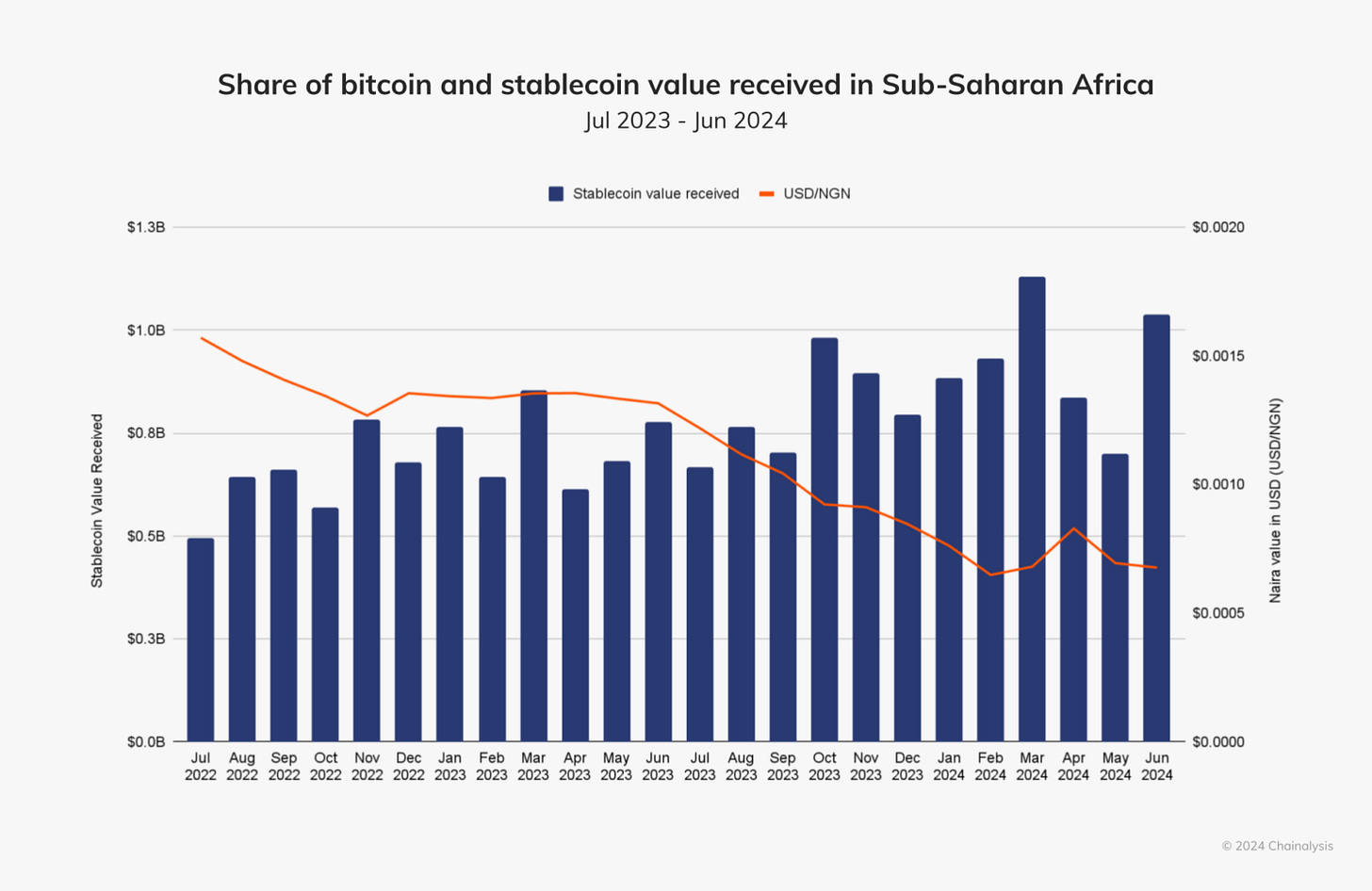

For the largest companies in the world, stablecoins are mostly a minor improvement on working capital (especially given that in many currency pairs they are orders of magnitude less liquid than the corresponding fiat pair) [6]. In contrast, for consumers around the world, stablecoins solve a hair-on-fire problem. This has only really been true in the last couple of years, and will accelerate whenever a country experiences a currency crisis or bouts of inflation. Consequently, the adoption around the world will not be uniform. You already see examples of this happening at a small scale. In Nigeria during bouts of inflation over the last 3 years, stablecoin adoption accelerated:

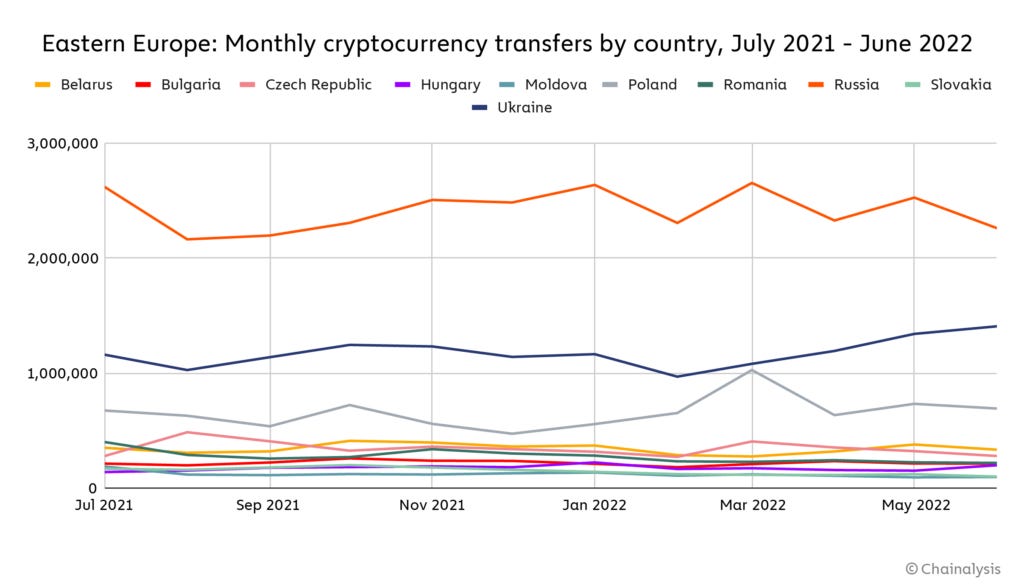

Similarly, in Ukraine, in the first 3 months following the start of the war, crypto transfers expanded by around 30%:

I suspect that given the recent shift to a more multipolar trading environment[7], we’ll likely see more economic dislocations happen to countries around the world with fewer multilateral institutions to help backstop them. Those dislocations will see the usual top down flight to quality as foreign investors pull out, and might also see a new bottoms up flight to quality as local savers flee to the relative safety of USD (via stablecoins).

The main reason I missed that consumers would lead the way is because establishment consensus typically comes from mainstream brand adoption. Your grandmother knows Apple, so if you said to her that Apple was using stablecoins to do something (literally anything), she would just assume it was serious/real. The secondary reason is that most of this infrastructure has been funded by vice, and (I’m not yet a super deep student of history) I can’t think of many cases where infrastructure built basically to enable speculation is subsequently used for core, everyday utility.[8]

Dollarization is here, it’s just not evenly distributed

Stablecoins are a permissionless way for retail and SMB around the world to save in dollars. Stated slightly differently, stablecoins basically expand the population that can save in a stable currency. Whatever your opinion about stables, it's uncontroversial that most humans, when they “save”, intend for their principal to retain value until they need it. As a result, “stability” is a feature of savings that stablecoins make available to consumers around the world. Many of those consumers cannot access that feature in their local currency (because their local currency loses value faster than dollars lose value). This attribute accelerates as stablecoin products become more interoperable/backward compatible with local economies (through things like stablecoin card issuing, billpay etc). This has several macroeconomic, political and policy implications that I think are pretty underdiscussed, some of which short term, and some long term:

Short Term effects of “self dollarization”

The best term I can think of for describing this effect is “self dollarization”; individuals around the world, opting first into saving in dollars, then transacting in dollars, then living in dollars, all onchain. [9]

Reducing local savings and draining local credit

Saving in dollars will first negatively impact saving in local currencies. This is already happening. A core feature of savings accounts that Americans have taken for granted for a very long time is that your principal is protected. If you live in a country that experiences bouts of inflation or crises, no amount of yield or interest on savings can make up for your hard earned income losing half its value. Stablecoins provide retail and SMB accounts a feature that their local banks can’t: effective principal protection. If your currency is losing 10% of value per year vs the dollar and you can save in dollars, it literally makes you richer over time. [10]

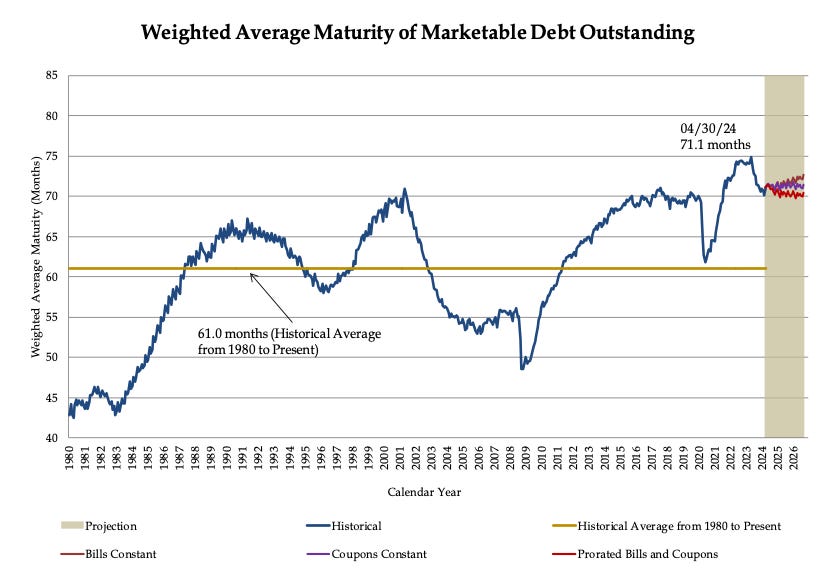

The secondary impact of this; self dollarization will probably also drain credit extension locally because that savings capital that’s now in stablecoins is, would otherwise be loaned out by the bank locally. This impacts lots of things; it reduces net interest margin for banks in these geos as they both have less capital to lend, and have to pay more to attract deposits. It also cycles that capital to basically fund US & European debt. As it does this, it also accelerates relative treasury demand to short term instruments[11]. As this source of demand grows, it likely makes the US/EU more susceptible to rate shocks as a larger proportion of borrowing needs to be refinanced in under a quarter than otherwise would be necessary.[12] Increasing borrowing in short duration Treasurys is already happening over the last few years; I don’t think this is purely about stablecoin demand being mostly short duration, but as stablecoins scale, they will contribute to this effect.

Transnational financial systems

We’re going to start seeing distributed financial systems that are made up of individuals around the world opting into the same unit of account. In the old world, there were several million people in a country, they shared the same border, and the unit of account, medium of exchange and store of value were all locally denominated.

In the new world, there will be millions around the world who share the same unit of account and store of value in dollars (or whatever reserve currency exists in their time), but their medium of exchange is locally denominated. This is because for years to come, most people in a geo will earn their income in local currency and will expect to be paid in local currency for goods and services.

This new financial system doesn’t yet have a functioning fractional reserve framework (where “deposits” can be used to extend credit. This means more stablecoin adoption in a country reduces available leverage in that country (there’s just less capital to lend). In addition, most onchain lending products today require you to pledge an asset like your BTC holdings and use smart contracts to manage margin. This means more credit is (relatively) available to those with more wealth, and general credit available worldwide will either shrink, or we’ll need to adapt with new systems for underwriting, servicing, collection, remediation etc to maintain the same proportion of unsecured credit. It’s tempting to think these activities will all move onchain, but fundamentally the deepest & most liquid credit markets in the world all have a long history of high functioning property rights and nonviolent dispute resolution, and many of those systems live offline (how are you going to repossess someone's car onchain?), and blockchains/stablecoins don’t materially change the trust/property rights framework in a country. My instinct is that the answer is a hybrid (onchain where you can, but local systems where necessary). But not yet sure.

Self Dollarization in the Medium to Long Run

One way to think about stablecoin adoption is as a real time feedback loop for inflationary pressures in a country. In this way people can avoid implicit wealth seizure via inflation, because they can respond directly, in real time, to inflationary government behavior, by rotating their savings into stablecoins.

Historically, rich people every in every country have saved in reserve currencies; there’s a reason the most affluent neighborhoods in cities like New York and London have a lot of homes owned by wealthy foreigners. Stablecoins change 2 things; first, they make this behavior permissionless; it’s very difficult for your bank to block you. Second, they make it fractional; you don’t have to be rich to save in dollars - you can start with $1.

This is a recent development that has really taken hold in the last 5 years, and will be exacerbated/accelerated by currency crises/bouts of inflation in various countries, and as a result the adoption will not be even/uniform (see my point above about Nigeria and Ukraine).

A different way to look at this is; permissionless adoption of stablecoins enables citizens to more quickly hold governments accountable for profligate monetary and fiscal policy. Governments who inflate away their ability/trust from citizenry to print money will experience the consequences more quickly. As more and more consumers realize they can opt into this new financial system, governments will more quickly experience capital flight in times of monetary stress. Governments will react to this differently. On the extreme end are countries like Zimbabwe that jail people for utilizing digital assets. On the other end will be countries like Argentina who have permissive dollar policies from a monetary perspective and embrace stablecoins and crypto. [13]

But I do think this will be a theme in the coming decade (highly polar government responses as stablecoin adoption accelerates).

The most disruptive long term impact is that a generation from now, there might be fewer currencies in circulation. This will at least be true from the perspective of volume in circulation, and may also be true of count. This isn’t all that crazy - 150 years ago the world had fewer currencies in circulation. The transition will likely not be smooth[14], but there’s no reason it can’t happen again. A less extreme variant is we’ll have a few “superscale” currencies and lots of subscale ones, as everyone who can, saves in dollars and everyone who must, saves locally. I think we dramatically underestimate the volatility that will come with these changes (politically, from a policy perspective, from a human perspective etc).

Monetary policy dilution

In 2019 while Mark Carney was the Governor of the Bank of England, he gave a speech at Jackson Hole where (among many other things) he said:

“ financial linkages have increased leading to a faster and more powerful transmission of shocks across countries”

If 350m Americans primarily earn save and transact in dollars, and an additional 350m people (just hypothetically) distributed around the world also save and transact in dollars, then a) US monetary policy directly affects all 700m, and b) monetary policy tools utilized by the local governments in those regions are by definition (At least proportionally) less effective. If your deposit base is shallower, you likely have to increase or decrease rates more than usual to have the same impact. In addition, your economy is now even more impacted by US monetary policy than before[15].

Dollars vs Tethers & the power of defaults

An underexplored topic is where belief/perception is embedded in the long run. If “all money is a matter of belief”, and you’ve grown up in a world where you saved in USDT, do you believe that the stability is brought to you by dollars or tethers? This might seem ridiculous to ask today, but humans often assume the things they grow up with are defaults they cannot change, and struggle to challenge or question the default thing unless under extreme duress.

Tether’s branding means that the default visual cue that holders see everyday is Tethers, not dollars. In the short term Tether is developing a reputation for being stable by maintaining its dollar peg and holding sufficient reserves in dollars to meet its redemption needs. In the long term it's not crazy that users/holders who grow up using USDT, might just assume Tether is a “currency” that is distinct from dollars.

An awkward financial crisis

No one can predict when, but the next financial crisis that we experience, whatever its cause, will have different mechanics than what most humans have experienced over the last 50 years, for several reasons:

Institutional trust is at or near all time lows, everywhere in the world. In the US, this has extended all the way to repeated challenges to the independence of the Federal Reserve

As the US government dismantles policy infrastructure and state capacity, its not super clear crisis response will have the same shape/force as in the last few crises.

Coordination between governments is probably also at an all time low

More and more of the world's payments and money movement is on some kind of instant rail, which means the mechanisms for bank runs (and currency runs to a lesser extent) to happen are now much faster than they used to be. It took 19 days for Wachovia to lose $18b of deposits. It took 2 days for SVB to lose $42b.

The growing adoption of stablecoins around the world means monetary policy from the US and Europe will have larger transmission effects into other countries than either the US or those countries expect, meaning, depending on your position as a policy maker, you are either overestimating or underestimating the impact of your monetary policy choices, and they will likely have second order effects neither country is prepared for

Stablecoins are in an intermediate position of regulatory clarity; socially they are more accepted and everyone knows regulatory clarity is coming, and it is partially here with the GENIUS Act passing. In parallel both banks and nonbanks are forging ahead and exploring stablecoin products and infrastructure. But the regulatory regime will take a few months to stand up. The next crisis is when all the risk management around these new products will be tested, and we’ll only know how good they are on the other side of the crisis.

Stablecoin issuers are a large and growing holder of treasuries; while the person at Treasury knows who to call at the Bank of England to have a discussion about reserves, is it clear who that person is at Tether/Circle/Paxos/First Digital? How do they look at the world? How do they react when liquidity evaporates for some period of time while redemptions accelerate? What do they do when spreads widen? What tools are available to them? This is a new “client” of the US treasury, whose needs are not exactly the same as another country’s central bank, or treasury, or an overseas pension.

At some point, a fiat-backed stablecoin issuer will collapse. Imagine it’s holders are spread around the world. Who is responsible for ensuring each holder gets their “deposits” back? Who makes sure the dissolution is orderly?

Most major governments around the world are fiscally quite stretched; the US/Japan/UK officially via government debt, China unofficially via bank debt. This already shows up in debt ratings, and will constrain the ability of policymakers to respond fiscally, as well as the effectiveness of their responses.

All of this is to say, it’s going to be weird.

The great weirding

There’s this Bruce Kovner line stuck in my head from a long time ago:

“I have the ability to imagine configurations of the world different from today and really believe it can happen.”

I think the way the world works today (and the way it’s evolving) is already quite different from how “we” think it works. We’ll only find out just how different the next time the system experiences shock. If you’re thinking about these problems or building solutions to them, or you just think I’m wrong about something, would love to chat!

Thanks to Dimitri Dadiomov, Justin Overdorff, Ben Milne, Zac Townsend, Nico Chinot, Temi Omojola, Meg Nakamura, Henri Stern, Zach Abrams, Aaron Frank, Amias Gerety, Peter Johnson & Ryan Lea for reviewing this in drafts.

[1] I use “Americans” and “Westerners” colloquially to mean people who live in countries with stable currencies relative to USD, who thus experience stable prices of everyday goods. One caveat: there are probably some countries with relatively volatile currencies that have relatively stable prices just because of their import/export mix (Australia comes to mind). For these countries the utility of stablecoins is limited even though the currency is volatile, because price volatility doesn’t bleed into their day to day.

Also I’ve only really excepted Japan here because i have a pretty limited understanding of it’s banking & payments system & infrastructure. These observations might also apply - I just don’t know enough to know.

[2] Just using speed as an example - I wrote in Time to Money about protocol changes (eg ACH to RTP) and would consider stablecoins a new protocol in the broad sense (narrowly there are lots of chains with lots of different features, but broadly I think of stablecoins as a new rail with a different set of attributes that are possible, even though the implementation might differ from case to case). In the US, I don’t believe the vast majority of consumers consider speed a problem, for the vast majority of use cases that they experience frequently. There’s lots of reasons for this: domestic transfers have lots of competition for instant “posting” (instantly making the funds available for the recipient to use), including both standalone applications like Paypal, Zelle, Cash App, and pretty much every challenger payment network/digital wallet option, options like Zelle that exist in their bank account.

Of course there are lots of edges where the banking/wallet/payment provider is using an old rail or slow rail (eg bank to bank transfers like doing a transfer from Chase to Wells over the ACH rail is one notable example) but this is not a function of the technology being unavailable or worse. It’s a problem of the provider choosing not to adopt the latest available technology, which is a hurdle the stablecoin use case has to cross anyway (driving adoption of installed base with existing distribution, or creating a new installed base). Your money has to be stored in an instrument which is using an instant rail in order for you to access that rail to begin with.

Crossborder cases are a little different for a couple of reasons. First, time to money in the consumer use case tends to matter far more to the recipient than the sender, because the recipient’s the one waiting to use the funds. It can matter to the sender as well if a late payment results in some real world/offline consequence (and I don’t want to downplay this) but in true consumer peer to peer cases, a lot of the traffic is social (between friends and family) or at best commercial adjacent. Second, the US is generally a net sender of remittances rather than recipient (both true in overall volume and transaction count). Practically, this means that a consumer in the US experiencing slow transaction speed is much less frequent than both a) as a sender or b) from a domestic transaction.

Bringing all this together; its just going to be a challenge for stablecoins to displace domestic payments on the basis of speed alone. There might be some other use case where the advantage is clear/obvious, but speed isn’t it.

[3] You might point to foreign exchange as something that’s been around for a long time, but next time you’re overseas try changing from local currency to dollars. It will be super expensive, have high minimums and the experience will be far worse than just using something like Sling Money or Dolar.

[4] Currency volatility by itself is a huge factor but not the only factor. The important thing is how the average person experiences that volatility in their life, and how it affects prices of goods people purchase daily. For instance something like Australian dollars are pretty volatile on the spectrum, but local prices are reasonably stable.

[5] My only caveat to the concept of permissionless is that, in times of crisis, governments (or the local powers that be, that are physically near you) are more likely to use violence to collect property, and fundamentally how much permissionless wealth you retain after than encounter is a function of how much violence you can resist or avoid. For all the adoption of digital & onchain products, property rights are still secured by violence and I don’t see that going away for a long time.

[6] I remember an anecdote from a stablecoin infra company mentioning that it took them several days to transact through a $3m Peso > USDT > USD position. In fiat markets this is a drop in the bucket.

[7] What I mean by this is, over the last decade we’ve shifted more and more away from the trade primitives/principles of the second half of the 20th century. If that period was underpinned by most of the world conducting trade mostly in dollars mediated by multilateral institutions, this more recent period is already seeing real competition from the RMB, and the Liberation Day announcement and the subsequent tariff deals mean more trade going forward will occur via bilateral country to country agreements. This shift was happening prior to 2025, but has accelerated post Liberation Day.

[8] A lot of the infrastructure that underpins stablecoins (and eventual institutional adoption) was essentially funded by gambling. The core use case for defi for a long time (through today) has been pure speculation; it's the casino in your pajamas, allowing you to play games of luck that you pretend are skill. The fees generated from consumers repeatedly trying to get rich quickly onchain funded lots of ecosystem players like CEX’s, DEXs and others. The businesses built around this speculative activity are now often very large financial institutions in their regions, and are core nodes in the stablecoin ecosystem being built around the world.

The other impact of defi was teaching consumers around the world crypto primitives; how to use a wallet, how to interact onchain, to avoid getting rugged, etc. Those same consumers are obvious early adopters of stablecoins and onchain financial products, and can do so using the same wallet infrastructure they used to speculate.

Gambling is profitable. This isn’t a commentary on defi/crypto. The fundamental human hormonal drives here are no different from slots or betting on horse races for most people - those just preceded crypto in terms of social acceptance. That being said, the infrastructure it has funded has the potential to stitch together a global financial system. Instead of being stitched together by large institutions in a consortium, or consumers within a single regulatory boundary, it’s consumers and SMBs around the world opting into utilizing the same unit of account.

[9] Dollarization typically refers to the adoption of the U.S. dollar as a country's official currency, either in place of or alongside its own currency. Historically a country’s political or policy leaders make the decision about adopting dollars (or not). Stablecoins make this process distributed and permissionless - a country’s president doesn’t have to make a decree, the citizens can just opt in directly.

[10] This is more true the longer your time horizon. In a country with even medium inflation, if you’ve been saving in a locally denominated pension/retirement over the last 20 - 40 years, the compounding inflation means your purchasing power in retirement has been gutted.

[11] The GENIUS Act codified that stablecoin reserves have to be held in Treasury notes/bills/bonds that are either issued with less than 93 days maturity or have a remaining maturity of less than 93 days: https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/senate-bill/394/text

[12] 65% of Tether’s overall assets as of their Q1 2025 attestation was in US Treasury Bills with a residual maturity of less than 90 days. This number is 75% if you include repo. For Circle (as of May 2025) 45% of overall assets were in Treasury Bills with a maturity shorter than 8 weeks.

[13] My only caveat to the concept of permissionless is that, in times of crisis, governments (or the local powers that be, that are physically near you) are more likely to use violence to collect property, and fundamentally how much permissionless wealth you retain after than encounter is a function of how much violence you can resist or avoid. For all the adoption of digital & onchain products, property rights are still secured by violence and I don’t see that going away for a long time.

[14] Carney’s comment that the “transition to a new global reserve currency may not proceed smoothly” is an understatement and I think very applicable to currency transitions of all types. Inflation is a continuous currency transition that degrades purchasing power, but shifts in the currency that’s being used are discontinuous, and degrade other types of power; if most of your savings are in a stable currency while your local currency goes into hyperinflation or is abandoned, you can find yourself suddenly becoming wealthy in your geo (more as a consequence of lots of your neighbors suddenly becoming relatively impoverished).

[15] The world is already quite dollarized. The current regime of floating exchange rates is less than 100 years old (as we slowly moved off gold) and even the prior regime of gold had more float in it than policy makers wanted. Even without stables much of the world’s central banks operate with soft pegs to the dollar (basically everyone that can, which is why currency regimes that fail to maintain that peg are so drastic — eg Nigeria and Turkey or even the pound in the early 90s) these pegs are stable until they’re not.

Stablecoins aren’t for Wall Street. They’re for the street vendor in Lagos, the freelancer in Buenos Aires, the refugee in Kyiv. They’re for everyone else.

https://divistockchronicles.substack.com/p/stablecoins-the-next-evolution-of